Good morning!

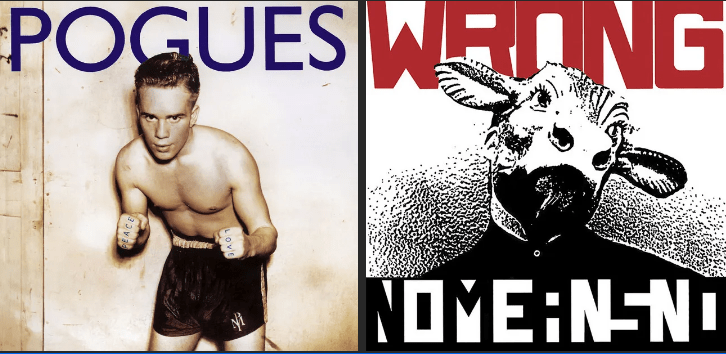

Today we’re taking a quick look at records from The Pogues and Nomeansno

Note: As many of you know, I recently wrote about a Best Record of 1989 challenge and noted that I’d occasionally write some of these up.

I’ve started doing some quick hits of each matchup and posting them directly to the page. Some will be longer, some won’t, and some might just be a handful of sentences. There’ll probably definitely be some typos.

Check ’em out and let me know your thoughts! Chin wags & hot takes welcome! Sharing and restacks are always appreciated.

KA—

The Pogues, Peace and Love

By the time Peace and Love dropped in the summer of 1989, the end of The Pogues was near. This was the moment the Pogues started to fall apart—and not in the sexy, myth-making way we like watching on rock docs. It was more like the ugly slow-motion collapse that happens in real life.

Everyone knew it was coming, but me. I wouldn’t find the band for a couple more years.

On a stereotypical dreary fall night in the midwestern college town where I live, a friend dragged me out for a night on the town. We’re gonna end up at a house party, he promised. The kind that you hear about from a friend of a friend whose buddy might know someone who actually lived there. This was an era of my life best described as “good music and bad decisions,” so of course I said yes. The night was as promised. To this day, I’ve never found a stronger Long Island than those served at Amy’s Cafe in Madison, WI. If you know of one, let me know. Actually, maybe you shouldn’t. Lol.

At any rate, we wind up at this house where a cover band is playing. I don’t know it yet, but they’re ripping through covers of The Pogues. I mean, tear the roof off the place, good. Of course, we’re a long way from the internet, and Shazam was still a cartoon character (or the name of an ATM if you’re from Iowa), so I finally had to ask. I was also the last person to hear about the band (The Kissers) and who they were covering. This could have gone all kinds of wrong, but the girl I asked was all too excited to tell me all about both. The next day, I went to Borders (RIP) and grabbed a copy of their Waiting For Herb record.

But before all of that, there was peace and Love. The record was their fourth, and (with hindsight) the one where the wheels start coming off. You could hear it in Shane MacGowan’s voice, which had gone from a cute, kinda feral to ghostly mumbling through a megaphone. It was the sound of a man’s liver and central nervous system teaming up to sabotage his own genius. You could hear it in the songs, too.

And yet—and yet—somehow, Peace and Love isn’t the disaster it probably should be. Even with all of that as a backdrop, it holds up better than many post-peak albums from great bands. Shane might’ve been fading, but the rest of the band came out swinging. “Young Ned of the Hill” and “Gartloney Rats,” both feel brand new and 200 years old (not derogatory). Philip Chevron gave us “Lorelei,” which aches in all the right places and blends melodrama with power pop without falling apart at the seams. If nothing else, you can say this: Peace and Love was from a band that still had something left to say—if not to prove.

Musically, they pushed the envelope just enough. A surprisingly jazzy, noirish thing is happening on “Gridlock,” there’s some rockabilly, and even (check notes) calypso? It’s messy, sure, but it’s a good messy. The messy that only happens when a band still gives a f**k—even if their lead singer’s interests are elsewhere.

Peace and Love isn’t Rum, Sodomy & the Lash or If I Should Fall from Grace with God. It’s not even Waiting for Herb (my fave). It may not be their finest hour. But it is the moment when the rest of the Pogues stood up, picked up the slack, and kept the thing going, if only for a bit longer.

NoMeansno, Wrong

We ended last week with a trip to Canada, and kicked this week off with some Fugazi. So it only seems fitting that we’d wind up here with a band that reminds one of a Canadian version of the band. Wrong is a wild ride through some unhinged riffs, drum beats that make no sense on paper, and choruses that range from “pop punk” to “screamed at you.” The ingredients make for a tasty mix, albeit one that’s an acquired taste.

My vote: I banked on a dollop of name recognition and a dash of sentimental value, and voted for The Pogues.

Any thoughts on either of these records? Agree/disagree with my takes? Which one of these would you vote for? Sound off in the comments!

Check out the full bracket here.

Info on the tourney, voting, and more is here.

As always, thanks for being here.

KA—

Leave a comment