Author and musician Chris Dalla Riva joins us to weigh in.

Photo by Jem Sahagun on Unsplash

Good morning!

Today we’re talking about AI. Or rather the crossroads of AI and music with our pal Chris Dalla Riva.

You don’t have to go far to hear about AI today. There’s everything from wistful think pieces to spicy takes and everything in between. It’s an equal opportunity target. If you’re anything like me, you’ve read a million takes both for and against its use.

Consider this the millionth and one.

Most of us have a strong opinion one way or the other; we either think it’s great or hate it. I’ve yet to see anyone say they don’t much care. Those strong thoughts are particularly divided in the art world/creator economy, where consumers are being overrun with slop and artists/authors are rewarded by having their work stolen and used to “teach” machines or compose hours of mindless music to be piped into fluorescent-lit hallways and your local Anthropologie.

Before we get too far, I want to be clear: I’m all for what has been referred to as the Three C’s: Consent, Credit, and Compensation. Those are largely self-explanatory, but the short version is this: if a tech bro is gonna hoover up an original idea, they should at least be paying the person whose synapses sparked it. A little credit would go a long way, too.

What does that look like in practice? I don’t know yet, but it’s not whatever we have right now.

I also want to be clear that most of the discourse so far has been binary. A lot of bandwidth’s been used in either/or discussions when it should be more of a “yes, and” or “yes, but” dialogue. For example, should a person take a 2-line prompt, generate a 750-word article “in the style of Kevin Alexander,” and pass it off as their own? I think most reasonable people would say no. What about non-native English speakers who use Grammarly to clean up grammar errors in their own words/ideas? Is that okay? I personally think it’s in bounds.

Much of the pushback has been because it feels like we’re being taken advantage of. We want to believe the person whose work we’re reading or listening to actually hammered it out on a notepad, keyboard, or instrument. Modern life never misses a chance to take advantage of us (or sell us more shit), and this often feels like one more in a long line of slights.

But what if the builder is transparent? Does upfront disclosure change the calculus? I think it does, if only because a consumer can then make a more informed choice. Pivoting back to music, that was a huge driver in the pushback against The Velvet Sundown earlier this year. The sting of catching someone trying to pull a fast one on you doesn’t wash away easily. If a singer tells you they’re using AI to give voice to their own words—now what?

Enter

Chris Dalla Riva. Chris writes the fantastic Can’t Get Much Higher which sits at the intersection of objective data and how it relates to the almost purely subjective world of music. He’s also the author of the forthcoming book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves, a data-driven history of pop music and a multi-year project that started with him listening to every number one hit in history. Put another way, he knows his stuff. I’m reading an advance copy, and can confirm it would make a great early Christmas gift.

Long-time readers may also recall Chris and me working on a project where he used Python code to extract data points from my Spotify history. He then used those to paint a picture of what I look like as a user, and share what I was “really listening to.” It was fascinating to watch come together. It’s also a situation where I think one could make a use case for using AI. After all, isn’t sifting through large data sets the sort of thing we want AI doing?

At any rate, today Chris brings us two real-world examples worth consideration. The first is an artist using AI to “sing” lyrics she herself came up with. The second is a fantastic breakdown of how it can be used to remaster/rerelease songs long thought lost to time.

Neither of us makes a declarative statement or pretends to have the answers. In my opinion, Chris’s article reinforces that more than anything, we need to collectively decide what’s acceptable and what isn’t, rather than outsourcing that to companies that only see us as data points to extract ad revenue from.

And with that, I’ll get out of the way and let Chris take the wheel.

KA—

AI Wrote a Popular Song. Is That Bad?

Have you heard about Xania Monet? She’s one of the fastest-rising R&B singers in recent memory. Released last month, her song “How was I Supposed to Know” was the first song by a female artist to top South Africa’s viral songs chart on Spotify in 2025. According to Billboard, that viral success helped her land a multimillion-dollar record deal.

So, who is this rising star? I’m not sure. She doesn’t exist in the traditional sense.

Xania Monet is the first AI-generated artist to land a song on one of Billboard’s charts. Unlike other AI-generated artists in the news, nobody is claiming that Monet is a real person. “Xania Monet” is a project by Telisha Jones, says Billboard, a “Mississippi woman … who writes her own lyrics but uses the AI platform Suno to make them into music.”

Scrolling through the comments on Monet’s songs, you’ll notice that people connect with it. And most have no idea that this is not a traditional artist. As someone who works in the music business, writes songs, and spends most of his free time chronicling the music industry, I’m all for songs people can connect with. Music can have power independent of the technology used to create it. Still, I think there are some looming ethical issues with fully AI-generated artists.

First, is this music copyrightable? A recent report from the US Copyright Office noted that, according to existing law, “Copyright does not extend to purely AI-generated material, or material where there is insufficient human control over the expressive elements.” Furthermore, “Whether human contributions to AI-generated outputs are sufficient to constitute authorship must be analyzed on a case-by-case basis.” Is setting human-written lyrics to AI-generated music enough human contribution to be copyrightable? It’s unclear.

Second, even if it is copyrightable, should the artists whose music was included in Suno’s training set receive royalties when Xania Monet is streamed? Given Anthropic’s recent settlement with book authors and pending lawsuits against Suno and Udio, it seems that the underlying music will have to be licensed in some way.

But let’s assume all of the intellectual property debates get sorted out. (They will at some point.) Then, is there an ethical issue with generating music with AI in part or in full? In the abstract, I don’t think so. Generative AI is a new musical technology in the same way that pitch correction and drum machines were once new musical technologies. As I note in my book, new musical technology always faces backlash. Still, when you think about the specific consequences of music made like this, things become dicier.

The Ethical Issues of Generative AI Music

I know next to nothing about Telisha Jones, the person behind Xania Monet. But let’s imagine for a second that I created Xania Monet. For those that don’t know, I am a 30-year-old White guy. Xania Money is presented as a Black woman. I think most people would agree that a White guy using generative AI to make music as a Black woman would be a bad thing. But I don’t see any world where that doesn’t happen without some sort of regulation around the usage of this technology.

Furthermore, generative technologies allow music to be made at an inhuman rate. Since July, Xania Money has released 44 songs. It is certainly possible for a human to release that many songs in a matter of months (see Morgan Wallen). However, products like Suno make it easy for someone to generate thousands of songs quickly. Unless it was choked off at some point in the distribution process, there’s no way streaming services don’t become flooded entirely with musical slop.

Anytime I levy these criticisms about generative music, I am often met with some claim that companies like Suno are “democratizing creation.” I’ve never bought this claim. Though you could argue that music has been democratized since the rise of upright pianos and low-cost acoustic guitars, I think it’s safe to say that true democratization came in three parts over the last 25 years.

- The proliferation of digital audio workstations, like Pro Tools and GarageBand, made recording at home incredibly cheap

- The rise of digital distributors, like TuneCore and Distrokid, drove the marginal cost of distributing your music around the world close to zero

- Mobile recording software, like BandLab, has made it possible to create musical masterpieces with nothing more than a phone

These three things –which were mature long before the rise of Suno and Udio–have made it possible for hundreds of thousands of songs to be uploaded online every day. That is democratization in action. The Xania Monet saga does not feel like democratization to me. It feels like more evidence for AI-generated songs flooding streaming platforms to be used in various fraudulent royalty schemes.

If I am such a downer on AI being used in the music industry in this way, then am I excited by any AI-based technologies? Of course. When I last wroteon this topic, I highlighted a few exciting tools. A year later, the most exciting use case remains stem separation.

On the Joys of Separation

One of the earliest known compositions of country legend Hank Williams is “I’m Not Coming Home Anymore,” a sad tale of lost love that sounds as complete as some of his more mature classics. The problem is that you can’t really hear it. Williams’ beautiful melody barely peaks through an avalanche of static. If only we could pull The Hillbilly Shakespeare’s voice out of that static.

Because of AI, we kind of can.

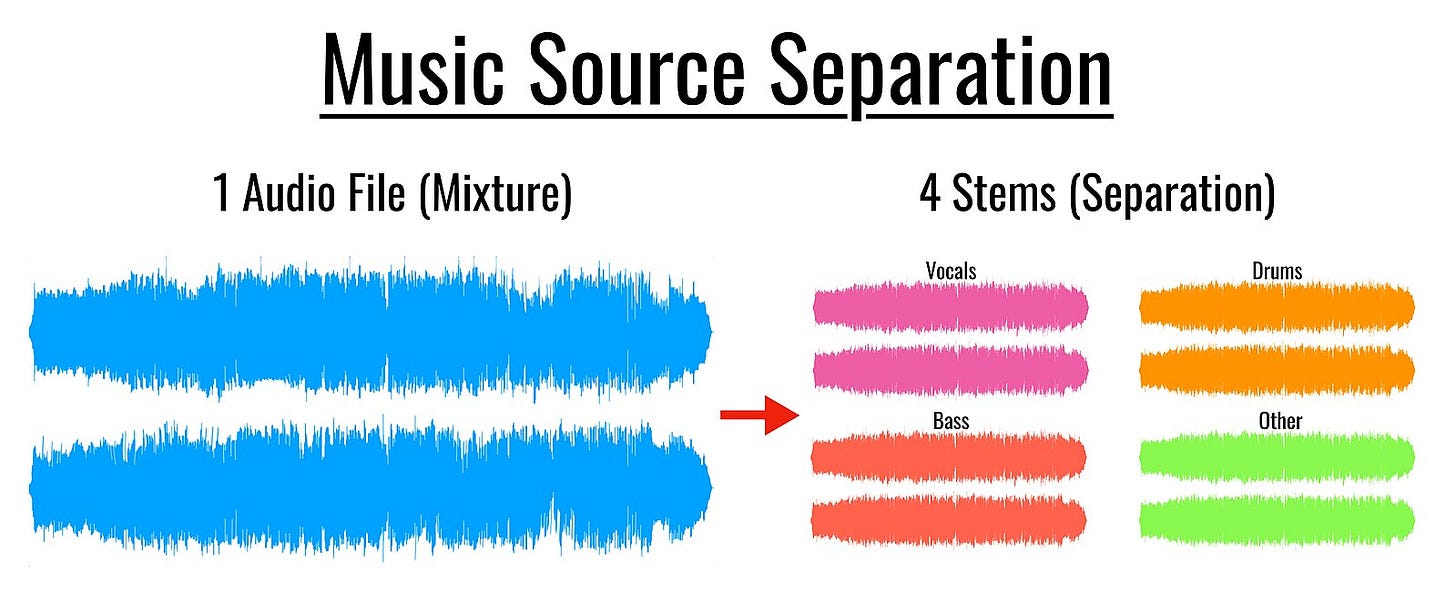

AI technologies have proven very adept at taking a mixed audio file and separating out all of the instruments. In the Hank Williams case, stem splitting technologies from LALAL.AI, Deezer, Serato, and a bunch of others could almost certainly get a clean cut of Williams’ vocal separated from the static and acoustic guitar.

We have already seen this technology used to great effect. In 2023, The Beatles released “Now and Then,” often noted as their “final song.” This was created from a low-quality home recording that John Lennon had made decades before. The Beatles’ team lifted a clean vocal from the recording using AI-powered technology. The living Beatles then completed Lennon’s demo.

This technology will become ubiquitous in the coming years. Not only will it allow us to preserve the past pristinely, but it will also make it easier than ever before for artists to remix, remaster, and reimagine other musical works.

As you can tell, I am much more excited by this musical technology than the technology that just allows us to generate songs for artists like Xania Monet. This new stem separation technology uses AI to solve a very hard problem. What Suno, Udio, and other generative products do is cool, but I don’t think it fundamentally alters the music-making process.

So what do you think? Are you all in, or are you on Team No F’in Way? In your view, are there acceptable carveouts? If so, what are they? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Thanks again to Chris for his time, and thank you for being here.

KA—

Leave a comment